Achieving higher accuracy in quantum chemistry and simulation with Fire Opal

Our customers and end-users are growing increasingly excited about the prospect of achieving practical quantum advantage in applications of quantum chemistry and quantum simulation. It makes sense intuitively—quantum computers obey the same rules as the systems users want to simulate and give a better representation of the problem can naturally simulate quantum systems better than classical computers.

As an infrastructure software company, we’re not in the business of placing bets on use cases – our customers know best what will deliver the most value for their businesses. It’s our job to empower them.

Our software product, Fire Opal, enables researchers and developers to push the limits of quantum hardware while making it easier to get meaningful results. By abstracting away complexity, Fire Opal enables you to focus on solving problems rather than managing errors and dealing with hardware-specific quirks.

Now, we’re introducing a powerful new feature designed to support applications in quantum chemistry and quantum dynamics: the ability to estimate the expectation value of an observable while benefitting from our powerful automated error suppression technology. These functions deliver greater accuracy and efficiency to these quantum use cases without any of the quantum-compute time overhead associated with error mitigation.

Why estimating expectation values is an important challenge

Quantum computers don’t return answers in the same way as classical computers. Instead, they sample measurement results from quantum circuits, producing a probability mass function over possible outcomes—a process known as sampling. Fire Opal’s execute and iterate functions currently return these raw probability distributions.

Frequently, implementing quantum chemistry or simulation algorithms requires calculating the expectation value of an observable, which tells you the average outcome you'd expect if you measured that observable many times on identically prepared quantum systems. Observables like energy, position, momentum, and spin are represented by operators whose expectation value tells you the most probable value of these physical quantities for a given quantum state. By computing the expectation value of an observable over time, researchers can model dynamic processes such as molecular interactions, phase transitions, and particle behaviors—insights that are often infeasible to obtain with classical methods.

The following diagram showcases the types of use cases that involve estimating expectation values versus ones where you would sample probabilities.

Calculating the expectation value of an observable is not as simple as implementing a standard averaging procedure. The most important consideration is the choice of basis, which is like a coordinate system for quantum states. The observable’s expectation can differ tremendously based on which projection you wish to measure. In addition, the measurement process itself also has a specific basis to consider. It’s typically up to the user to figure out which bases matter and then compile all the relevant versions of the circuit needed to deliver the correct information.

There’s a large penalty in execution as well as preparation. Since quantum measurement collapses the state, you can only get one piece of information per shot, meaning that in order to estimate expectation values of multiple observables, you need to measure each circuit multiple times. Each different basis required—sometimes thousands of them for even modest qubit counts—-also means executing a slightly modified version of the circuit. This execution overhead adds up quickly!

For example, consider the task of estimating the energy of a state under some Hamiltonian H. You need to prepare the state first and then measure it in any Pauli bases that appear in H. If the circuit has just one qubit then the max number of such bases is three. However, if the circuit has two qubits and H has all possible Paulil terms, you'll need to measure in all nine non-commuting bases (XX, ZZ, YY, ZX, ZY, XY, YX, YZ, YX). The number of bases grows exponentially with the number of qubits and the complexity of the operator we wish to estimate, creating significant opportunities for error or, if optimized, improvement.

This isn't the full picture. Users must also choose the best compilation for the device and apply error-reduction strategies to achieve high-quality results on current hardware.

The process has been burdensome—preparing and compiling circuits, selecting the right basis, and reducing hardware errors manually involves trial and error, often taking days to weeks and costing tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars in quantum runtime. We knew there had to be a better way.

A fast and effective approach to simulation

This is where Fire Opal’s estimation functions come in. Users simply provide circuits preparing target states and a set of target observables. The new functions—estimate_expectation and iterate_expectation—automatically decide the best way to run the circuit and the optimal configuration of measurement bases to calculate expectation values and variances. Fire Opal provides an easy way to orchestrate the many circuits that need to be run in support of these new applications while automatically leveraging high-performance error suppression to achieve higher accuracy.

In addition to the obvious benefit of simplicity, Fire Opal delivers another key advantage: reduced compute overhead. One way to improve the quality of any averaging routine on noisy data is to average more and more runs. That’s effectively what “error mitigation” does—it leverages clever tricks to continuously increase averaging to help “see through” the noise.

Fire Opal takes a completely different approach.

Fire Opal uses a deterministic form of error suppression to prevent errors from occurring in runtime by modifying circuits at the gate and pulse level and implementing high-efficiency, error-robust compilation. Using these techniques, Fire Opal can deliver performance benefits without the expensive execution and postprocessing overhead needed in error mitigation.

When considering thousands of different measurements that need to be performed, the reduction in compute time delivered by Fire Opal can be enormous. For instance, error mitigation providers cite runtime overhead ranging from 30 minutes to 7 hours for basic circuits—now none of that is required, saving you time and money. Fire Opal is verified to reduce those overhead penalties by at least 100x.

Using Fire Opal’s new abstractions, algorithm developers can streamline the development of applications in these areas through abstraction and push to greater problem sizes and complexity through high-efficiency error suppression.

Fire Opal is device and hardware provider-agnostic, which means you can use these functions across supported backends. If you’re an IBM Quantum user, you can also leverage the Performance Management function’s estimator primitive to access the same performance benefits.

Real-world impact: Simulating complex molecules with greater accuracy

Simulating the time evolution of quantum systems is a critical capability across quantum chemistry, condensed matter physics, and high-energy physics. Whether you're modeling molecular dynamics or simulating lattice models, achieving accurate results on real quantum hardware has long been a challenge—primarily due to noise.

Fire Opal’s new estimation functions redefine what’s possible, delivering unparalleled accuracy even at scales where classical methods struggle.

To measure the impact of Fire Opal’s new estimation capabilities, we simulated the time evolution of physical observables under a non-classical Hamiltonian. Specifically, we used the Transverse-Field Ising (TFI) model, a common benchmark for evaluating quantum hardware performance. This model is represented by the following equation:

The structure of J (non-zero elements) is given by the underlying graph/lattice topology.

Most previous demonstrations of the TFI model were constrained to a line topology—the simplest structure for execution on current quantum processors, but far from the most relevant for real-world applications. Exploring more complex and interesting topologies means the ability to solve more relevant use cases, but it also results in tougher circuits that typically suffer from much more noise.

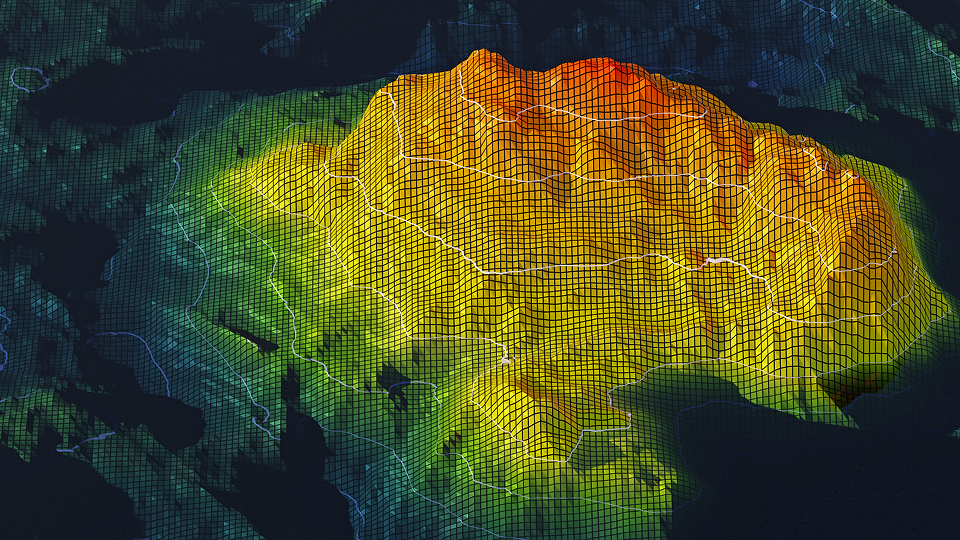

We wanted to push the limits and explore more complex and realistic topologies, some of which are shown in the following image.

As a challenging test, we ran our benchmark on a 35-qubit triangular chain, as shown in the prior image, with uniform couplings, J, transverse field, h, and a ratio of h/J = -0.4. We start from the ‘all-zero’ state and follow the evolution of the Z magnetization over up to 20 Trotter steps. The h/J ratio above was chosen as it far exceeds the trivial limit of J~0, and at the same time, the evolution of the Z magnetization shows a non-trivial pattern that oscillates and spans across the full range of possible values. Such a rich pattern serves as a good test for the quality of the quantum circuit execution, as noise tends to dampen such patterns.

Unlike a simple line topology, this structure introduces nontrivial connectivity constraints—in the case of the 35 qubits triangular chain, 18 of the qubits are each connected to four others, making circuit compilation significantly more difficult.

Since there aren’t any IBM Quantum hardware devices today with topologies that easily map to this structure, compiling the circuit to match the device is nontrivial. Additional SWAP gates are required to connect the qubits that aren’t connected.

The impact? When evaluating quantum circuits, the number of two-qubit gates and the number of layers— groups of two-qubit gates applied simultaneously in a circuit—are two indicators that correlate with the amount of error that occurs during execution. At 35 qubits and 20 Trotter steps, transpilation with QiskitRuntime’s optimization pass results in a circuit with 3,849 two-qubit gates and 300 layers! For comparison, a 35-qubit, 20-Trotter step circuit of the much simpler 1D line topology requires fewer than 1,400 two-qubit gates and just 80 layers. This means that even a simple change in the topology of the simulation can shift an execution on hardware from simple to highly challenging.

Despite the complexity, Fire Opal’s new estimation functions deliver highly accurate results, even in circuits exceeding 3,000 two-qubit gates.

Fire Opal’s error-suppression pipeline runs each circuit in about 1 second, with the full simulation completing in just 30 seconds—including data loading time. According to published documentation, common error mitigation routines, such as Probabilistic Error Cancellation, would require several hours, days, or even weeks to run this set of circuits.

With Fire Opal’s powerful new estimation functions, you can simulate quantum systems of increasing complexity, all while avoiding the pitfalls of noise. Even better, this pipeline works on any algorithm and any supported device—without requiring additional configuration or hardware characterization on your end.

How to estimate expectation values

Fire Opal’s new functions are tailored for different types of workloads to help you manage the job submission and provider platform intricacies so that you can focus on the application.

The estimate_expectation function can be used for a single job with a list of circuits, observables, and an optional list of parameters. This is ideal for use cases like short or sparse-time evolution or fixed-time expectation estimation.

The iterate_expectation function is useful for use cases where you need to repeatedly calculate the expectation value many times over several jobs, either due to an iterative workflow or a huge batch of circuits. This function manages the optimization of compilation and device queueing on your behalf, so that you can reduce the total amount of experimentation time required. Similar to the stop_iterate function, you can indicate that you’ve finished your workload by calling stop_iterate_expectation.

Check out our documentation to view all of the ways you can submit jobs on quantum hardware.

Unlocking new possibilities in quantum simulation and chemistry

With the introduction of expectation value estimation in Fire Opal, researchers and developers now have an even more powerful tool to push the boundaries of quantum computing. Whether you're modeling complex molecular interactions, studying quantum dynamics, or simulating physics beyond classical reach, Fire Opal helps you achieve higher accuracy while minimizing noise—without any additional overhead.

By abstracting away hardware-specific challenges and automating error suppression, Fire Opal ensures that you can focus on your application, not the challenges of today’s quantum systems. As quantum hardware continues to evolve, these techniques will be critical in demonstrating real-world advantages across industries.

Ready to take your quantum simulations further? Sign up for a free Fire Opal account today.